In 1940, the federal government took Norman Baker to court on mail fraud. What they really wanted, however, was to stop him from claiming he could cure cancer. This was their best way in.

Courtesy of the Museum of American History, Cabot Public Schools

Norman Baker’s watermelon seed, brown cornsilk, and clover leaf tea

Baker wasn’t a doctor, according to The New Yorker. "He was, among other things, a radio broadcaster and a former vaudeville magician who had become rich selling a musical instrument called the Air Calliophone."

Probably an acquired taste, that air calliophone.

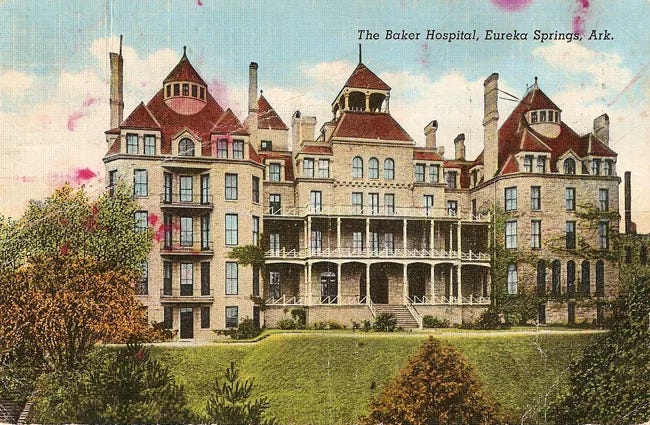

Sometime after those somewhat queer careers, Baker met a certain Dr. Ozias, who claimed he could cure cancer. Smelling an opportunity, Baker sent five patients his way to test out the claims. Ultimately, two of Ozias’ employees jumped ship and went to work for Baker, who must have been a charismatic fellow. And that’s when Baker began claiming he could cure cancer. He set up a hospital in Eureka Springs, Arkansas and an institute in Muscatine, Iowa. What was he serving up exactly? From a 1940 ruling from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth circuit, we learn that:

"Maud Randall, employed at the Baker Hospital, was given a formula by Norman Baker, from which he instructed her to brew tea for patients, the formula being watermelon seed, brown cornsilk and clover leaves."

Yep. brown cornsilk. Is that the little tassel part at the top, as opposed to the yellow stuff covering the actual kernals? Anyway, it must have tasted terrible, and if medicine is supposed to taste terrible then that must have been convincing to patients.

Staff had no idea what they were doing

Court documents also show there was little diagnosis, and little understanding on the part of the staff of how to, um, practice medicine:

"There were no microscopes to be found in the hospitals...no pathology attempted. Dr. J. W. Miller...gave the same hypodermic injections to patients Number 4 and Number 5, but did not know what either contained. Dr. J. W. Cotner...gave injections Numbers 4 and 5 hypodermically for everything that a patient had regardless of the disease."

No word on what happened to patients Numbers 4 and 5, but it probably wasn’t being cured of cancer. One injectable mixture turned out to be "....18 of one per cent hydrochloric acid, .03 per cent of salt, and a trace of phosphate, the rest being water." And the other was "...25.53 per cent glycerin, 28.4 per cent carbolic acid, and the balance alcohol." Not exactly precision medicine.

The siren song of a “truth teller”

Baker's allure went beyond the promise of a cure for cancer. He presented himself as the anti-establishment truth-teller, the guy with the real answers, not one of those so-called mainstream doctors (sound like anyone you know?). He wore white or purple suits and drove a lavender car. He said that the usual treatments for cancer at the time—surgery and radium, for example—and all other remedies and treatments recommended by members of the American Medical Association "would not and could not in any event cure cancer," but that in 1929 he alone had discovered and developed the real cure.

Eventually, the law sniffed out a fraud and chased the case.

Back to the court case…

Why did the feds take Baker to court over mail fraud? It's because they couldn't win a case against him for extracting money from hopeful patients with false claims. They could show that he had sent misleading information, and unapproved drugs, through the U.S. mail, which is a crime.

Again, from the court documents, we learn that the way he promoted the cure—prolifically—ultimately took Baker down:

"[His] magazine, first issued in December, 1929, stated that the five test patients had been cured…These test patients in fact died of cancer...In 1936, Baker published a book entitled, "Doctors, Dynamiters and Gunmen," in which he again made claim to having favorably treated these test patients, all of whom had in fact been dead from cancer several years. This book, and circulars and magazines, containing in vivid fashion these false claims to a cure for cancer and other diseases, were sent through the United States mails in great quantities." (emphasis mine)

Baker was indicted on mail fraud in 1940.

Pro tip: don't send your false advertisements or drug hoaxes through the mail.

Oh, and try not to bother his ghost…

His story doesn't end there. Today, some visitors claim the Crescent Hotel in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, where Baker hawked his cure, is now haunted. The ghost you want to avoid the most? Baker's, according to KATV-Little Rock:

"He seems to be the apparition that is the most unfriendly, you might say. And you do not want to provoke him, we know that much. He has been provoked in the past and it wasn't good," said Erin Davison, a server and ghost tour guide at the Crescent.

Those creative feds!