The 1880s "Rest Cure:" milk, bed, electricity

Charlotte Perkins Gilman and a paternalistic prescription that wasn't so restful

We can all use some downtime. But if you were a woman in the 1880s with depression or fatigue, you might have been prescribed something much more radical: the "rest cure."

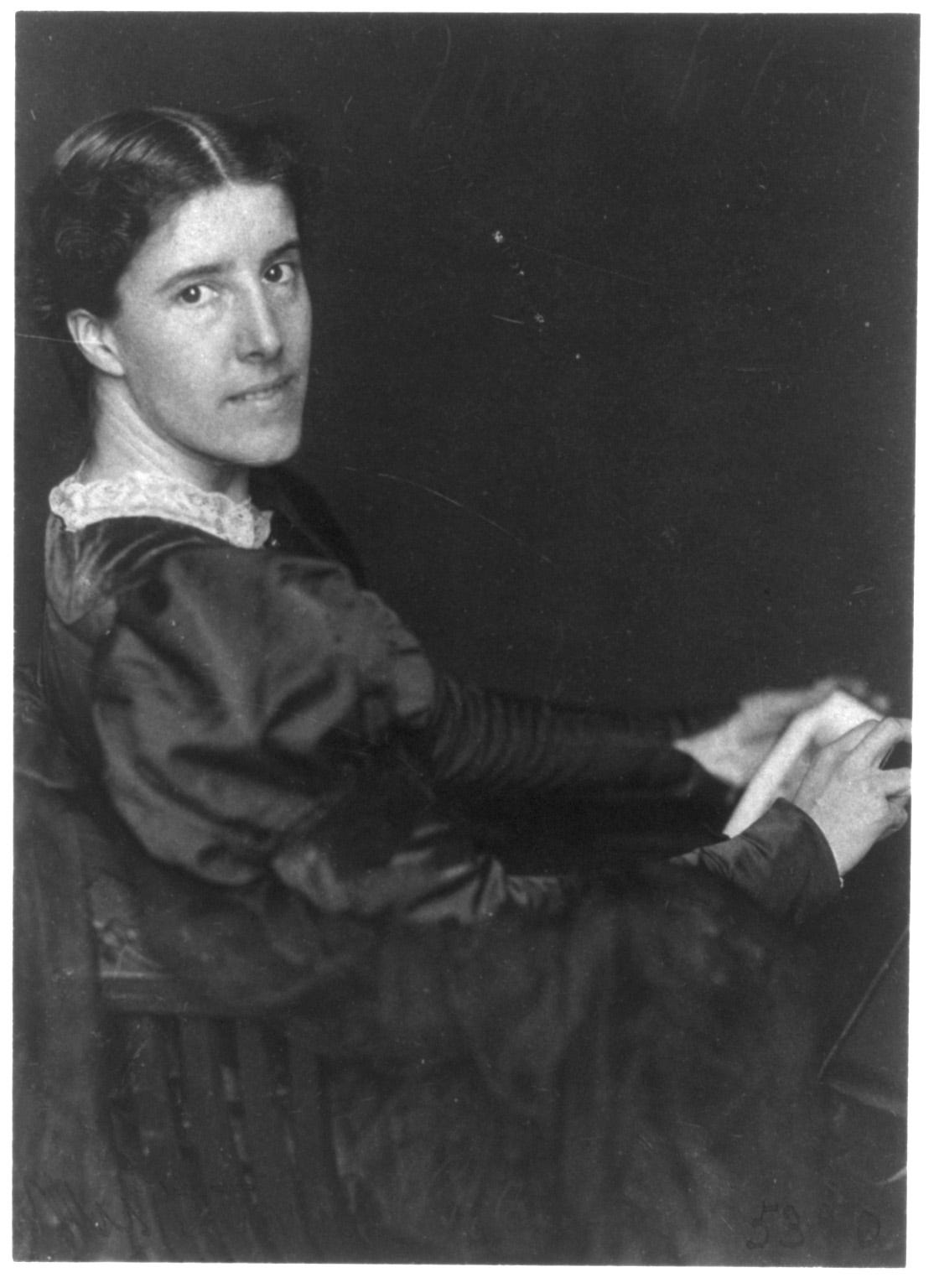

Charlotte Perkins Gilman ca. 1900

A prescription for women’s ailments

In 1877, S. Weir Mitchell, a prominent neurologist, published his treatise Fat and Blood: And How to Make Them, which outlined in minute detail his “rest cure.” It was a meticulous prescription for mostly neurasthenic or anemic women, neurasthenia being a loose term for fatigue and depression. The idea was that a couple of months of this routine would reset the body, pave the way for a more vigorous constitution, and fatten up a feeble woman. It was also a paternalistic judgement of the worth of her complaints and her ability to heal without round-the-clock supervision.

This was the very treatment prescribed to Charlotte Perkins Gilman. She didn’t take the full course, described below, but was affected enough by it to write the famed short story, The Yellow Wallpaper, about a woman taking the “rest cure” and slowly going mad. She later sent it to Mitchell, which I love. Like a kid sticking her tongue out at a bully.

The details are bananas.

A diet of rest and milk. Under Dr. Mitchell's rest cure, everything about a woman's day and night was monitored and measured, including her diet. She rested up to 24 hours a day. She drank a diet of milk and, eventually, some broth and bread.

Movement, massage, and electricity. Mitchell recognized that lying in bed for so long might cause muscles to waste away. He had some protections against that. Patients were allowed to sit up for 15 minutes at a time, twice a day. Eventually some could go for an hour's walk but immediately return to rest. All received vigorous massage and sometimes the application of electricity to their limbs.

Fat and blood. Mitchell's goal was to increase their blood (the quantity? the strength? It's hard to tell from his manuscript) and ensure a healthy weight. Those two forces, he reasoned, would restore a woman to health.

Isolation and removal. One of the cure's most important, and possibly cruelest, features was meant to break the pattern of selfishness he claimed these women created in their own households. Mitchell often sent his patients to live elsewhere and confined them to a single room. A nurse often slept in a cot nearby to enforce the orders. The nurse could read to her, but only the most agreeable news. Visitors were mostly forbidden. Most were not allowed to read to themselves, sew, or write.

A patient lies on a chaise-longue, while a nurse brings her some refreshment. Wood engraving by J.C. Griffiths after G.G. Kilburne. Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection. CC.

The reverse effect

The trouble was, of course, that Mitchell was beating the physical body into submission along with the mind. He may have had his patients’ best interests in mind, and certainly studied the impact of his treatment with the scientific rigor of the time. But perhaps he misinterpreted his findings. It was the worst possible treatment for Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

"For many years, I suffered from a severe and continuous nervous breakdown tending to melancholia — and beyond. During about the third year of this trouble I went, in devout faith and some faint stir of hope, to a noted specialist in nervous diseases, the best known in the country. This wise man put me to bed and applied the rest cure, to which a still good physique responded so promptly that he concluded there was nothing much the matter with me, and sent me home with solemn advice to 'live as domestic a life as far as possible,' to 'have but two hours’ intellectual life a day,' and 'never to touch pen, brush or pencil again as long as I lived.'

I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near to the border line of utter mental ruin that I could see over."

I'm so thankful she defied doctor's orders and picked up a pen again. Gilman went on to write Women and Economics, one of the most important works of the early years of the women's movement in the U.S. She wrote several more books and launched her own journal, The Forerunner.

The Rest Cure today?

I would never wish Gilman’s treatment on anyone. Twenty-four hours in bed with no intellectual activity at all would drive the best of us crazy. But…I must say that a day or two all to myself, with no visitors or distractions, and just a great book, might work wonders. “Hello, room service?”