In the 1880s, John Flavel Mines, a beloved New York author and cartoonist, was desperate to get sober.

In a North American Review article from 1891, he wrote:

"For twenty years I had been a victim to the disease of drink...I have as much will-power as the next man, but my will was a straw in the grasp of this horror...I had battled for years, had gone voluntarily into exile in homes and asylums to escape my enemy, and only in late years recognized the fact that drunkenness was a disease...No one who has not been similarly cursed with the disease of drink can know the joy of the moment in which my cure came to me as a fact. I do not believe, I know, that I am cured, and am satisfied as to its permanency."

Mines was talking about what happened after he took the Alton-Brown train line at Union Station to Dwight, Illinois, a tiny prairie town just an hour from Chicago. His destination: the Leslie E. Keeley Institute, where the former Civil War surgeon turned entrepreneur and inventor administered the Bi-Chloride of Gold Cure for Inebriety.

How about not just sober, but cured?

Addiction is hell. Recovery can feel slow or unattainable. Who wouldn’t want a relatively fast, easy cure (compared to years of relapsing)? To one person, a cure might mean the ability to drink with no consequences. To another, it might mean the desire for drink or drugs is gone. Keeley promised the latter. And he claimed a 95% cure rate. Pretty impressive, no?

Keeley's treatment: roll up your sleeves for a secret shot

Keeley said his Bi-chloride of Gold Cure for Inebriety could cure "dipsomaniacs" (Victorian lingo for alcoholics) and "morphine eaters" permanently. The treatment involved four injections a day, two ounces of a complementary tonic every two hours while awake, and a four week stay at one of his institutes. Those who needed small amounts of alcohol to withstand withdrawal received a bottle of whiskey until they didn't desire it anymore, which Keeley said happened in less than 48 hours.

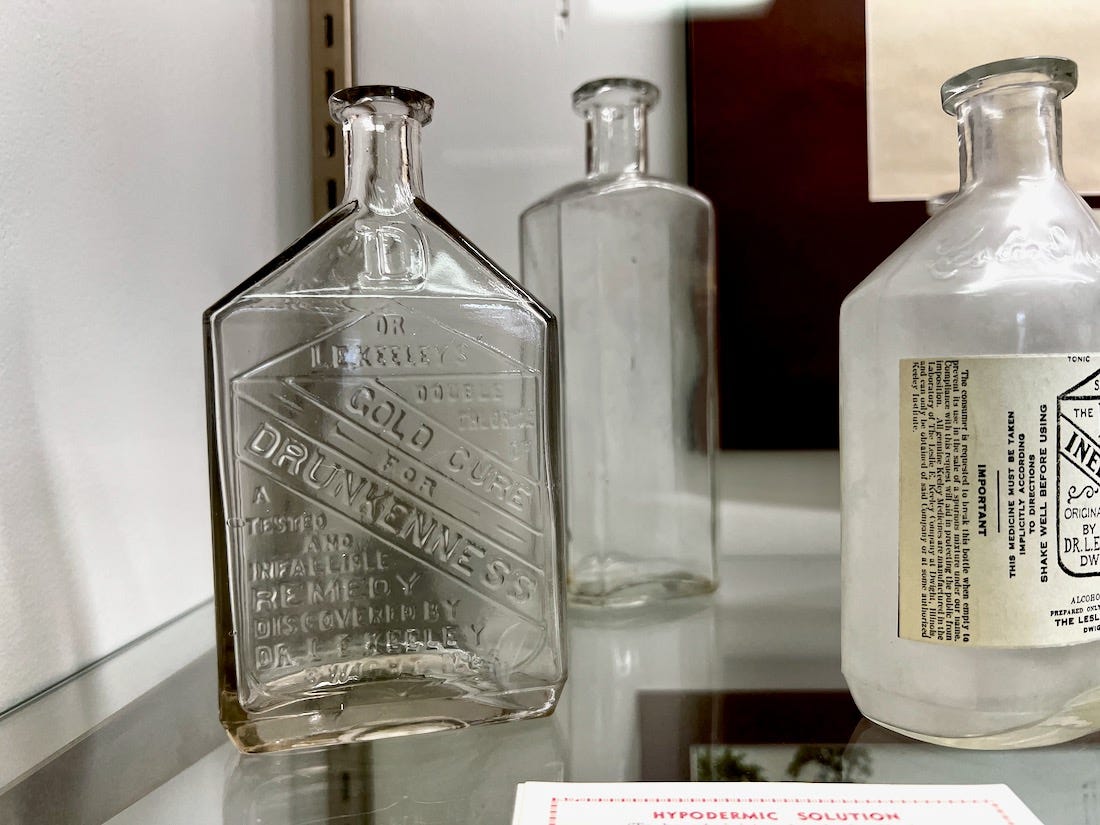

Bottles of Keeley’s Bi-chloride of Gold cure displayed at the Dwight Historical Society. Photo by Kristin Gourlay.

Thousands took the cure in Dwight, many penning newspaper testimonials and memoirs, proudly proclaiming, "I've been to Dwight!" Keeley soon established institutes in major cities across the U.S., where former patients established Bi-Chloride of Gold clubs, holding something like proto-AA meetings.

Journalism luminaries Nellie Bly and Joseph Medill stoke the fire

The World sent the country's most famous female journalist, Nellie Bly, undercover to try the Keeley cure. And Chicago Tribune editor Joseph Medill sent a group of men to Keeley's Dwight institute, challenging him to cure "the worst drunkards." Both wrote glowing accounts.

So, was it the real deal? And if so, why haven't you heard of it?

I have some theories. But first...

"A fraud and a quack"

Some physicians of the time, including members of the relatively new American Medical Association (AMA), railed against Keeley. They called his cure a sham and chastised him for keeping its ingredients a secret. Keeley countered that only he knew how to administer it and that revealing the ingredients could jeopardize his methods. The state of Illinois even revoked his medical license for a time, likely at the prompting of the AMA (he got his license back a few years later). Chauncy F. Chapman, M. D., writing in the Chicago Medical Recorder in 1893 declared:

"The patient should be in a sanitarium or retreat which ought to be situated in the country with pleasant surroundings; roomy, airy bedrooms, a good cuisine, and scientific physicians in attendance who will study each patient as an individual and carefully watch him during the whole course of treatment...There should be no secrecy or charlatanism about the treatment...As regards the prognosis we must be guarded. The medical man who will guarantee the cure of any pathological condition, no matter how simple, is a fraud and a quack."

Other critics said he was out to make a buck. And yes, he made some bucks.

Lab tests and insults couldn't stop a steady flow of patients

Many sent the formula to chemistry labs, which couldn't identify every ingredient, but most found it contained small amounts of strychnine, atropine, alcohol, but no gold. Some of these ingredients increased metabolism or turned your stomach. Many patent medicine makers of the time used them and said a small amount of alcohol was a necessary preservative.

Still, hundreds of thousands took the cure, including some women, rolling up their sleeves to receive injections of a formula whose ingredients they didn't know, four times a day. Hundreds of thousands must have walked around with little glass bottles of the tonic, clinking in their pockets and purses. And hundreds of thousands experienced the community of other people with addictions, without restraint—a new concept at the time.

Keeley died in 1900, leaving no children and beefy inheritance for his wife. His institutes carried on, the secret contained, for a few more decades. But their popularity began to dull by the early 1900s.

Leslie E. Keeley, public domain.

Here's what I think happened

Recovery is about more than meds. People weren't "cured." The formula probably put them off drink or morphine for a while because the medicine and the thought of using made them sick. I think it was the routine, the community, and the relief of knowing they had a disease and were not moral degenerates that were the true tonics.

News of public failure spreads fast. Some Keeleyites famously relapsed. About John Flavel Mines, our beloved author and cartoonist, the New York Times ran this obit in 1891, just months after he had written about being cured: "He was found drunk in the gutter Wednesday last, was committed to the workhouse on Blackwell’s Island, and died there yesterday morning."

Medicine grew up. Few were willing to tolerate a secret formula. Imagine receiving an injection today from a doctor who told you he couldn't reveal the ingredients but that you would be cured.

The belief was real, and sobriety can be too. That people felt cured, I don't doubt. That they returned to relieved and joyful loved ones, I don't doubt. I doubt they all stayed sober. But I believe they tried and that some may have kept trying all their lives.

I believe addiction is a lifelong disease, but recovery is possible and can last a lifetime. In my world, you're just one drink or pill away from losing it all. But thankfully today, there are so many paths to treatment. If you're struggling, may you find one now.