Have a listen to my conversation with U.K.-based Caroline Rance, author of the fabulous Substack The Quack Doctor. You can tell by the title that we’re mining similar veins, no? She’s got some great stories about magic bullets of the past, including mummia (or, really, mummy juice), a man who tried to fish out his own tapeworm, and the incredible advertising moment that was Satanic Liniment.

Listen to our chat or read the edited transcript below. And be sure to subscribe to Caroline’s Substack!

Thank you, Caroline!

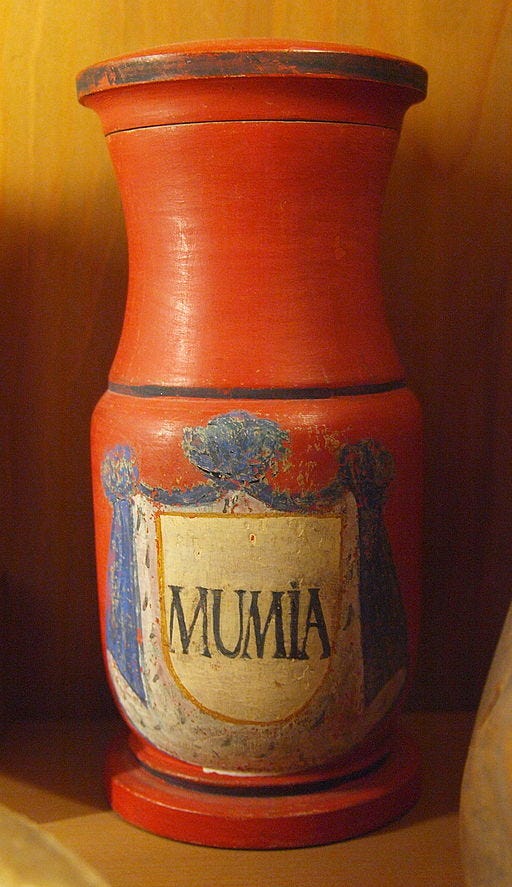

Apothecary vessel (albarello) with inscription (MUMIA) dating to 18th century at Deutsches Apothekenmuseum Heidelberg, Germany.

Transcript

Kristin Gourlay: I love the story about mummia. There was an interest in powdered Egyptian mummy as a miracle cure in the 1500s. Can you tell that story?

Mummy juice: the cure-all

Caroline Rance: So this came about as a bit of something that was lost in translation. Way back in ancient history in Persia, there were substances that were naturally occurring in the mountains. And that was called mummia because mum meant wax, and it was a waxy substance. It was like a bitumen type of thing, and that was used medicinally. And then in about the XII and XIII centuries, Europeans started to get the idea about this and to translate the texts of the medieval Muslim physicians. That's where it got lost a little bit because there was one guy, Gerard de Sablaneta. He translated the Middle Eastern physician Al-Razi. Gerard described mummia as the substance found where the bodies are buried. And he was talking about the liquid of the dead, saying that it was quite similar to the pitch substances.

And that then got perpetuated with people thinking that Egyptian mummies could heal you of various things. So then people were actually taking these Egyptian corpses and initially using any liquids that came out of them, but then instead of that, starting to grind up the actual flesh and use that as a medicinal substance.

Kristin Gourlay: I'm having a visceral reaction to this right now.

So then people were actually taking these Egyptian corpses and initially using any liquids that came out of them, but then instead of that, starting to grind up the actual flesh and use that as a medicinal substance.

Caroline Rance: It is a bit like cannibalism, really, in a way, people are actually consuming these dead bodies. But obviously, there's only so many Egyptian mummies to go around. I mean, there were certainly a lot, but it's quite impractical to get hold of them, especially if you're in Northern Europe. People started to see it as a business opportunity that they could create their own. Whether in Egypt or in France or wherever, people would start using deceased people, maybe executed criminals or similar, and to use that as fake Egyptian mummy.

Kristin Gourlay: What did they say it could cure exactly? What was the point of taking mumia?

Caroline Rance: It was a huge number of conditions and diseases, but mostly things to do with bruising. If you were injured and you had a big bruise, they would say that you would take that internally, and that was supposed to help the bruising. As we know, lots of bruises will just get better eventually. It can take a while, but they will get better. So that made it look as though it was working. But people would use it for all kinds of things, really. It was a bit of a cure-all.

Kristin Gourlay: Could we move forward in time and talk about another one of your stories? This one takes place in the 1750s, and it begins with a tapeworm.

Fishing for his own tapeworm

Caroline Rance: Yeah, I like tapeworm stories. I don't really know why, because when I was a kid, I had a bit of a phobia about worms, earthworms and things like that. But I find their life cycle is quite fascinating, and I keep finding these strange tapeworm stories from the past to talk about. But this particular guy lived in France. He wrote about this in 1749, but the whole process had started much earlier than that. He believed that he was being plagued by tapeworms. I think he got quite obsessive about the whole thing, really, because he was trying absolutely anything he could in order to try and get rid of these worms that he believed were inside him.

So he was going to ordinary doctors and they were prescribing all kinds of things like blood letting. They thought he had some blood disorder instead of worms. And they assured him that, yes, he was now better and he could go off and be quite happy, but he still felt that he was still suffering. So he then went to somebody else. He was trying things like watercress drinks and starving himself. He tried laxatives.

And he then went to somebody who he describes as a madman at Auvergne. He doesn't say who this person was. He just describes him like that. And he decided that the patient had dropsy. So that's what we now call edema. So he was quite swollen. So that meant that he would have to undergo a procedure called tapping, which meant that they would actually pierce the swollen flesh and hope that some fluid came out. And that didn't work.

So he then decided to take matters into his own hands. He tried some of the quack remedies as well, and they didn't work. So he started just wandering about the countryside, eating any random herbs that he could pick up because he figured that if he died of poisoning by something, it was probably no worse than the existence that he was having to put up with. So he was eating all kinds of things. And I think some of them did work a a little bit, but not really enough for his liking.

But he got even more obsessive, and this is the really gruesome part of the story because he—

Kristin Gourlay: It's already gruesome!

Caroline Rance:—Yeah, that was nothing compared to what he did next. So he actually made some little hooks with three prongs, a bit like a fishing hook, but three prongs on it, and he threaded that onto a lead bullet and swallowed it. So he wanted to try and get the worms up in these hooks, and that would hopefully kill them, and then they would exit his body, hopefully without any damage, which he was prepared to take the risk of, being very much damaged inside.

Treble fishing hook

Supposedly, according to this story, it did work to some extent. He was bringing out these big sections of worms And then he thought there's still a way to go. So he got one of these hooks, which he adapted his design and made it serrated to make it even more deadly to the worms. And he swallowed that one, but he kept it on a string outside his mouth because he intended to fish the worm out and pull it back out through his mouth. And he did have some sense at that point and realized that it was going to be way too painful and that he would probably just scratch his entire esophagus.

But he swallowed that as well. And then the worm did come out the other end, complete with its head and everything. So by that point, he felt that he was cured.

And we know of this story because he initially wrote to a French newspaper about it. And then The Gentleman’s Magazine in England found that interesting, and they published an English translation of his letter. He was recommending what he'd done as a safe and effective remedy for tapeworm. He thought, until somebody discovers something better, this is my experience and what I recommend.

Kristin Gourlay: What I love about your Substack is that your stories are so narrative. It's much more than, 'here's this weird thing I found.' It's the story of someone's journey, trying desperately to find a cure for something, and the sometimes very tragic or fascinating twists and turns of that journey, especially when quacks are involved. I would just love to know a little bit about your research process for putting those narratives together.

Finding stories in nooks and crannies

Caroline Rance: Yeah, I have done quite a bit of archival research in the past, especially when I started writing on this subject. But there are so many wonderful digitized resources these days that I primarily use those now. There's things like newspapers. A lot of my stories stories do come from newspapers. Of course, you have to be careful because the journalists of the past would make stuff up just as much as they do nowadays. It is about cross-referencing lots of different versions of stories and seeing if you can work out and analyze which is the most likely to be what really happened. But there's also lots of the books that you would find in libraries have now been digitized. There's things like the Medical Heritage Library, which, sadly, is not being updated anymore, but there's still loads of things that they have digitized over several years that you can access there. I use Ancestry.com quite a bit as well. I know it's for family history, but it's really useful for finding out the background of some of the people that I'm looking at and seeing how they grew up, where they came from.

Kristin Gourlay: Do you have any other really favorite stories of some quack remedies?

Satanic liniment and “mental sunshine”

Caroline Rance: I've got one which is not yet on my Substack. It's on my other website. This is a thing called Satanic Liniment. This was introduced in 1914, and it was really just a deep heat rub thing. It contained capsaicin, which is extract from peppers. You put it on if you had arthritis or something. It probably did heat you up a bit and maybe it had some effect. But the marketing was just really unusual because they would have this logo of Satan standing there on the world. I assume it was something to do with the fire the heat of the medicine. But they also had one called the Satanic Tonic Laxative as well.

It's a strange way of advertising something and thinking that people are going to want to use this product advertised by Satan.

Kristin Gourlay: It's something I wouldn't want to take.

Caroline Rance: It's a strange way of advertising something and thinking that people are going to want to use this product advertised by Satan. But they said that constipation was pretty much the cause of everything that could possibly be wrong with you. If you took the Satanic Tonic Laxative, then that would clear you out and leave you with mental sunshine, they called it.

Kristin Gourlay: That's a good outcome!

Why do you think people are so susceptible to falling for quackery?

Caroline Rance: People can be quite vulnerable when either they're ill themselves or perhaps their child is ill or somebody that they love. And quacks offer to solve your specific problem. So that's true of lots of marketing, actually. But for conditions, especially if there's not an outright cure, a doctor might be able to do something for you, perhaps ease pain, but they can't ethically say that they will cure you if that's not possible, whereas a quack can offer that false hope.

Anyone can fall for a quack

I think it's very understandable that people are attracted to these narratives. I don't really like to say that people fall for quackery because I think any of us can be gullible, even if we're usually skeptical. If that targets our specific complaint, whether it’s a specific medical condition that we're having difficulty getting treatment for, then they can be really tempting.

I don't really like to say that people fall for quackery because I think any of us can be gullible, even if we're usually skeptical.

I think we still have our fair share of quacks today. You look at Facebook adverts and things like that, they're always promoting some dodgy supplement and things. But I think things have changed in the sense that we do have the protection of more regulation nowadays. But what has changed is the way of disseminating that information.

Rather than having somebody standing in the marketplace, perhaps, and spouting their spiel about their wonderful remedies, or perhaps advertising in newspapers, we've now got this very immediate way of communicating with people through the internet. So it allows people to come together from all across the world, people who have the same beliefs or have got an idea that some particular therapy is going to work. They can share their experiences with each other and perhaps encourage each other to believe in things that maybe they'd be a bit more skeptical about if they were just on their own.

Kristin Gourlay: It has been so lovely to link up by Zoom and have a chat with you, Caroline Rance. You're the author of The Quack Doctor, and I'm obsessed with your Substack, truly.

Caroline Rance: Great. It's been really lovely to talk to you. Thanks so much for inviting me.

Note: Magic Silver Bullet will be coming to your inbox on more of a biweekly basis.

Share this post