Interview: Lessons from the 1911 Manchurian plague

Ming Yang, from Health Checks on History, on how we forgot about masks, and why there's a glimmer of hope for future pandemics.

What can we learn from past pandemics? Tons. But we have to be willing to look back.

That's what Ming Yang, an editor at Nature Medicine, has done. In a recent post on his Substack, Health Checks on History, Ming wrote about lessons from the 1911 Manchurian plague epidemic, which killed 60,000 people.

Ming's Substack is right up my alley, with its focus on the intersection of public health and history, and so is Ming, a warm and generous scholar. He spoke with me from the U.K. about the post, "Plague masks worked, then we forgot," which tells the story of a 1911 pneumonic plague in Manchuria (a part of what is now China) and how authorities managed to contain the outbreak with basic public health tools. The story matters now because the U.S. is so increasingly polarized over the response to infectious disease that we seem to be forgetting that those basic tools work.

Here's my interview with Ming. Enjoy! And please visit his Substack, Health Checks on History.

Set the scene: what was it about the Manchurian plague of 1911 that made it so dangerous?

"It was a plague that allowed human-to-human transmission, which is called the pneumonic plague. So the Black Death, that was bubonic plague, transmitted from rodents to humans. The 1911 plague was actually one of the very deadly events, because it could be spread by people coughing, being in close contact with others. And in Manchuria at the time, there was a lot of environmental upheaval—rivalries between the Quin dynasty, with Japan, with foreign powers. It was also an area with a lot of mining, which put people in close quarters. So these were the conditions that allowed the plague to fester into a proper epidemic.

How did authorities respond?

"I think what was quite unique about the pneumonic plague was that it was one of the first times in which there was what we call now a multi-sectoral response. So that means you're having many, many different interventions to basically to tackle the plague, which is very reminiscent to the COVID pandemic. So previously, in other outbreaks, the responses were usually quite piecemeal. They ranged from wearing masks because people believed in things like the miasma theory. There were maybe some quarantines here and there. But I think the aspect with this pneumonic plague was that the authorities were using a range of approaches. They used quarantines, they had "plague passports" so that people, if they tested safe, were allowed to move freely with a passport. If not, then they were confined to carriages and wagons. They also had checkpoints, which was part of the quarantine process. And they had face masks and even PPE (personal protective equipment, like masks and gloves). This was probably the first modern version of PPE ever, during the Manchurian plague. There was also a very extensive education campaign across communities in Manchuria.

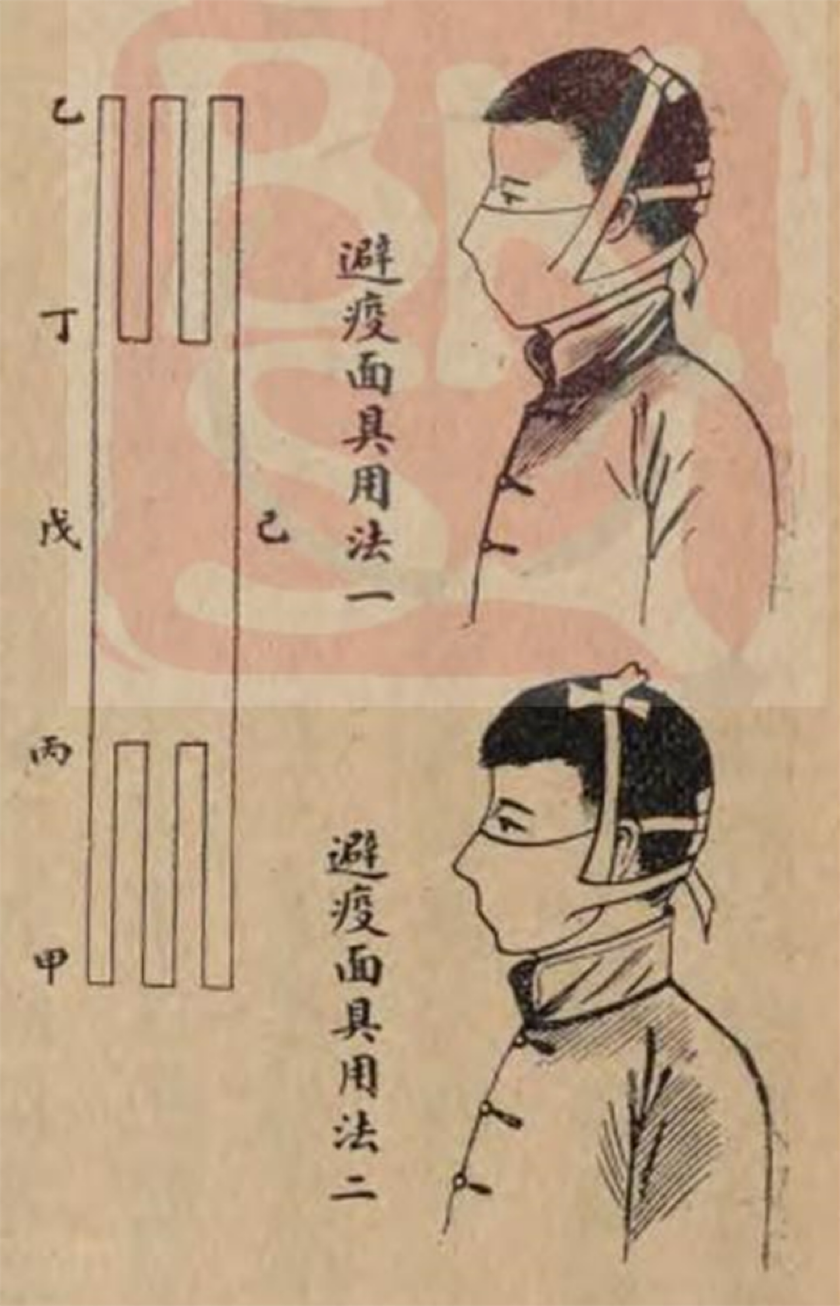

Diagram and instructions on how to wear an anti-plague mask in two ways. 避疫而具用法一/二 translates to “Method 1/2 for using masks to prevent the epidemic. Source: Yu Fengbin 俞鳳賓. Zhonghua yixue zazhi 中華醫學雜誌 [China medical journal] 4, no. 2 (1918): 76–79.

What do you think we have forgotten about those public health endeavors, something that could help with modern day pandemics?

"What I was quite surprised about is the fact that there was disagreement about wearing face masks from the beginning of the COVID outbreak. The symptoms of COVID were basically coughing, fever. So there were very strong signs it was a respiratory virus—an important reason to wear a mask. My mother is a nurse in the National Health Service here in the U.K., and at the beginning of the pandemic she wore a face mask. No one in her hospital was doing the same. They were even discouraging her from wearing face masks because they thought she was scaring the patients. Also there were a lot of people who had concerns about the efficacy of PPE during the time. At the start of the pandemic, the WHO, the World Health Organization, actually didn't recommend the use of face masks in public because they felt that there wasn't sufficient evidence until June of 2020, despite the fact that we knew it was a respiratory illness early on.

“So the fact that countries like the UK and the US were implementing face masks late, this gave a mixed message to the public. And that's also why you get a wave of people in the public who are very much against face masks, and especially also things like lockdowns—although the lockdown situation is a bit more complicated because of the fact that there is evidence of lockdown impacts on mental health and education.”

What else can we learn from the Manchurian response--you mentioned an international treaty?

“I think one of the big breakthroughs is the fact that there the first World Health Organization pandemic treaty was negotiated with over 194 WHO member states. That was the first time that this many countries of different regions, different political backgrounds, all came together to actually have a framework for addressing the impacts of a future pandemic, to try to coordinate a more joint, cooperative public health response. And that was why I wrote in my blog about the fact that the Manchurian plague actually was the one of the first times when to deal with infectious diseases, they actually had delegates from 11 countries all come to Mukden (now Shenyang), which is in Manchuria, and having a first international plague conference. And that was one of the very few pivotal moments that led to these international collaborations.

“When there is a pandemic, one of the most important things is collaboration and cooperation between countries in terms of data sharing, timely recommendations for what to recommend in an outbreak response—such as wearing masks—and coordinating between different countries around air traffic control so that the response can be as effective as possible.

“Obviously, this is not going to be easy because there's a lot of political difference, there's a lot of political rivalry, and right now it's even worse between countries now than even in the last 20, 30 years. But it is really important that countries do come together and put political differences aside and really have a stronger message, even to the public, around new infectious disease threats.”

This is indeed such a polarized moment. Do you have any hope for our next pandemic response?

“In my line of work, I deal with a lot of depressing things, especially with what's happening in the US. At the journal where I'm an editor, we literally have updates for what's happening this year in the U.S., with RFK's anti-science policies, reform of the NIH, and dismantling of the CDC. We know the people of the U.S. are very concerned, and most are very supportive of vaccines. So it's not the fact that everyone in the public is skeptical of public health measures, it's the fact that there are a couple of people at the top who are making some very deleterious decisions. Next year there are midterm elections and people can vote for a stronger Congress that will ensure accountability of the country's top health officials.”

“So I think there's a glimmer of hope here, and I think it's really just a matter of time before sentiment changes and people come to trust public health measures again.”

Ming Yang is the author of Health Checks on History and an editor at Nature Medicine. He's based in the U.K.

Thanks Ming!

Wow! I'm surprised about some of the mask stuff!